|

Here's a possible articulation solution for Telemann's B minor Fantasy for solo flute, end of first movement. The 't can either mean closing the sound at the end of a note or to start a note. It means the tongue is back on the palate and ready to go. The alternating blue and red is just to make it easier to read. Notice also I prefer to use a "d" for the low notes for a better and more secure sound production. Remember that how you work your air and the characteristics of particular notes are also important aspects in articulation, so it's not just reliant on the syllable alone. A "t" could potentially also be useful for a soft effect, such as for the high A# at the end since it helps to bring clarity to the otherwise dull-sounding note. With all these differentiations of t, d, r and in combination with variations on how/when to stop the sound, one can truly bring out the "Vivace" of this movement - "lively". I think liveliness through articulation is one of the hallmarks of baroque music and you can see here how effective this is. If you'd play this movement just fast and without any of these nuanced details, then you're missing out on a lot of fun and so is your audience! Try it out and let us know what you think! To hear this passage from a practice session, refer to my video here:

0 Comments

Addendum from previous post: to create that flying sensation and brilliant staccato in the higher register, try tonguing further back than you would for the mid/lower registers! Your embouchure needs to be well set for the high and work with the lower lip to create space for the notes to sound. The lips also need to be strong enough so you don't end up pinching, which often happens in the beginning. It's about developing that very refined muscle memory to create a glow✨ in the sound.

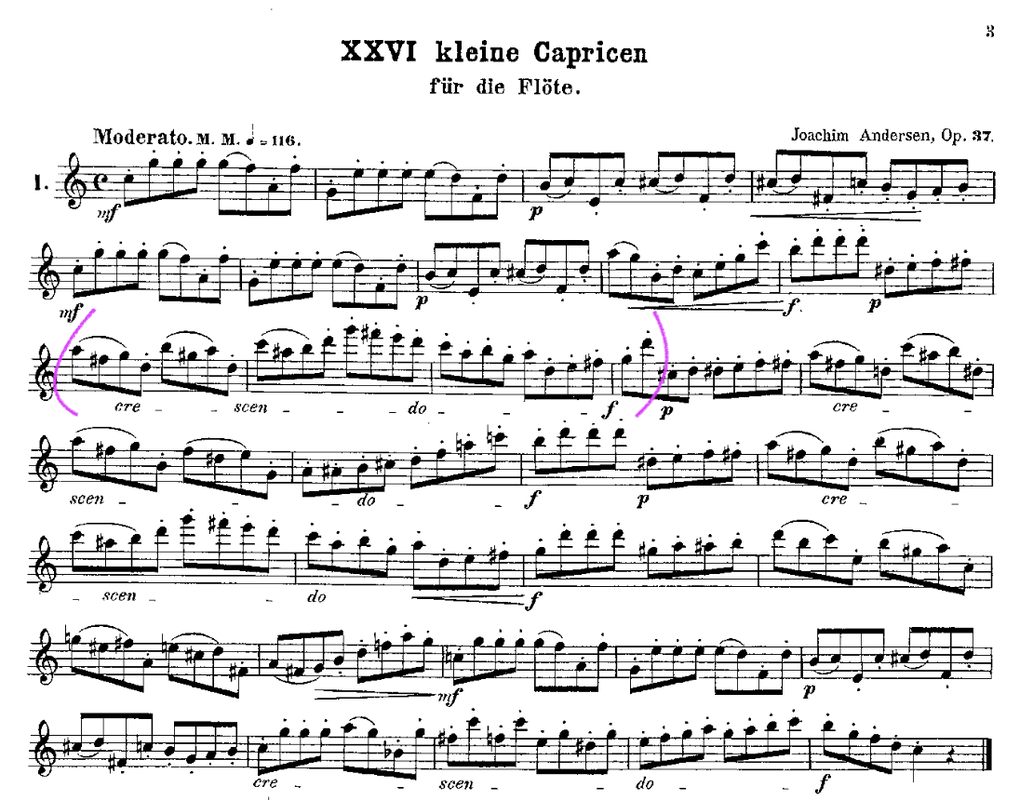

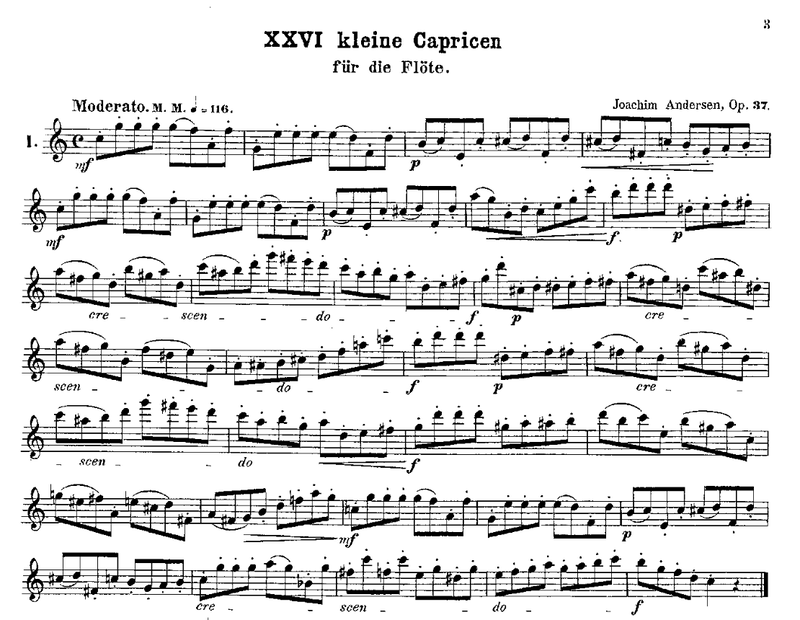

The C major etude from Andersen's Op. 37 is just such a fun piece to play. In fact, I really don't see it as an etude in the normal sense, but one could easily play this as a nice little encore piece.

In my recording, I've taken up the tempo quite a bit compared to what's indicated on the page. I encourage you all to always make expressive decisions in whatever you play. (technique and expression go hand in hand, but we'll get into that another time!) In this particular etude, Andersen is asking us to examine the flexibility and fluidity in our airstream in the presence of mostly staccato notes, with some occasional slurs mixed in. Staccato, although short, should still show direction and phrasing. Different types of staccati can be achieved by shaping your breath differently: - Should the air (sound) linger on or really cut off? - And how long should the sound go further? - How do dynamics play a part in the passage? Should the notes get louder but all stay equally short, or get softer but linger a bit in the air? (and many other exciting permutations in between!) - How do you direct your embouchure to create an effect? Do you need to slightly shape your lips to create that extra fine tapering in the sound, or have them stay put to have equal sounding lengths? There isn't just one kind of "short", and short doesn't mean less in any way. Short notes can give an incredible sense of depth and brilliance - this is especially important for the high register as often the notes up there can lose body, sounding dull and flat, especially if you have to play them short. Make sure you open your throat/chest/nose as much as you can, imagining the sound coming from deep down. Resist the temptation to simply blowing more and see if you can use the slowest and least amount of air to achieve a warm "glow" in the sound. I've also found, the more the hands can let go, the more your sound will ring. Always keep observing, listening, and feeling. When everything clicks in, it'll feel great! As you can see, articulation is not just about the tongue, but also very much connected to so many aspects of our playing technique. The fun is to be able to piece everything together and at the end, see what you can do to make that final personal touch to create your signature interpretation! In my case, I envision trapeze artists defying gravity and tumbling across the air with this piece. As I'm preparing for our upcoming Bach St. Matthew Passion workshop, here's a little music analysis which I feel is exciting to share:

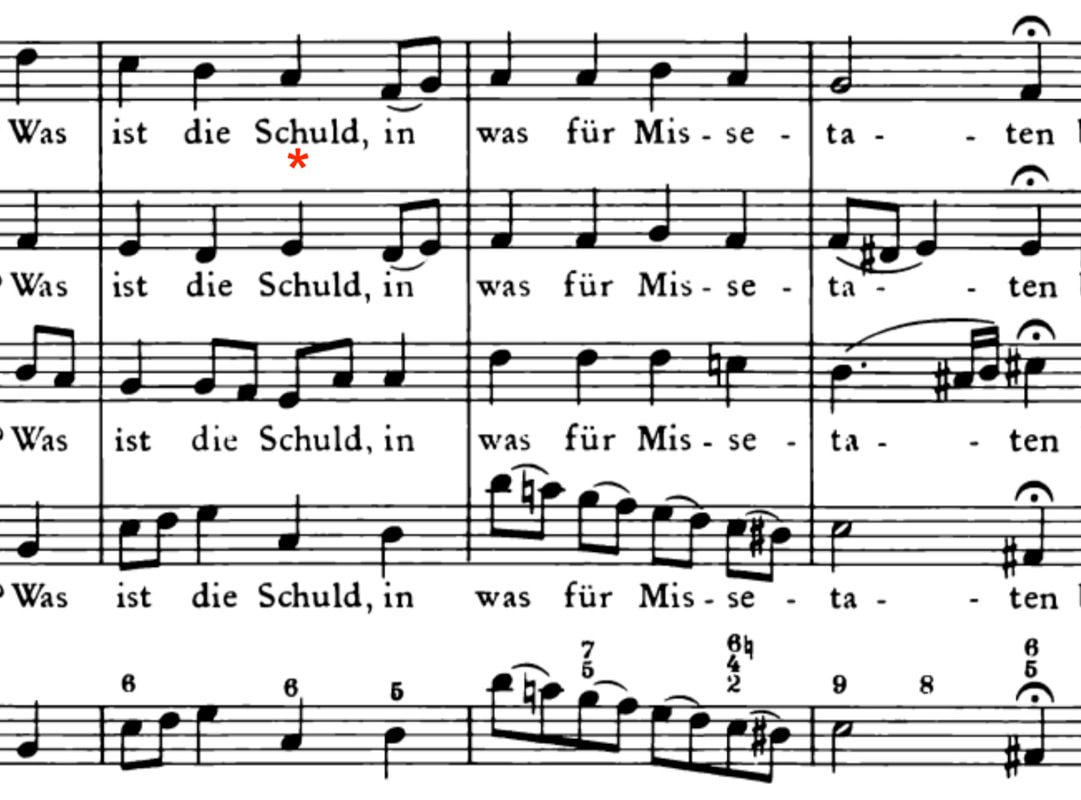

Besides the solos in this monumental work, there are these many seemingly "easy" chorales to play. However, these chorales were very important as they would have been well-known to the congregation. They brought everyone spiritually together, including the layperson who might not understand the meanings of the big arias. Conveying the text through the albeit simple melody is the key in playing them. Take a look at this excerpt from "Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen". (Dear beloved Jesus, how have you transgressed) from his St. Matthew Passion. There are 3 things that are happening around the word "Schuld" (guilt in the legal sense, or crime): - It's an important word in the text - the "d" in "Schuld" is more like a "dt" in German pronunciation which gives the word a definite closure - There's a comma afterwards So all these things make the end of that "Schuld" note slightly detached from the rest, the sound has to close before going on, creating an "articulation silence", in order to reflect those same nuances in the text. In baroque flute playing, it is common to use the technique of closing the sound with the tongue. Going on directly or making the sound legato with the next note will degrade both the literal and emotional intent of the passage. The concept is simple and yet it can have such a profound effect on us players as well as on our listeners. This is just one of many, many instances in the endless connections between music and text, and it's a whole lot of fun to discover them! Playing chorales this way will then become meaningful and create a defined musical presence in the performance. There was a request for me to share some thoughts about articulation in the music of J.S. Bach. Thanks for the suggestion! I don't think what I'll talk about here is exclusively only for Bach, but I do think that Bach or German baroque music in general has certain characteristics which demonstrate quite clearly my concept. Click on the video below to listen to three ways of playing the first measure of this Bach violin sonata, each with a different combination of tonguing and breath work. You may want to turn up your volume and hear it a couple of times to fully recognize the subtle but important differences. from J.S. Bach's Sonata in B minor for Violin and Obbligato Harpsichord I'm currently preparing this piece for a performance and honestly, I've been feeling stuck with that first measure for awhile! And while I was using varied articulation, there was something about the tonguing and the breath that didn't quite match up, or wasn't refined enough. It sounded stiff and dull just like Example 1 or 2.

Basically, I would suggest here the tonguing pattern T DR(it) 'TR D(it). R is like the Latin hard R. The (it) or apostrophe signals stopping the sound with the tongue, which is very important in baroque music to give a clear shape to phrases, and also establishing metric stability. I'd tongue the second T (note E) a bit lighter than the first T (F#), but I also realized I can create a nice gesture on the E if I gave more of an impulse with the breath there, which is what you hear in Example 3. It propels the melody forward and gives it a good swing. Not all T D R's are the same, a T could be slightly more forward or slightly more backward in your mouth. Stopping the sound has also its variants. On top of all that, there's the question of how you use the breath to further sculpt the sound, which means working on flexibility in directing the air. I like to think of articulation as sculpting and carving the sound like a sculptor working with an extremely fine knife. This image works particularly well with German baroque music as it echoes the music's defined, perhaps slightly edgy structure. It brings clarity to the counterpoint. It fits the language well if you're working with a singer. Do let me know what differences you hear in the above examples! |

ABOUT THE BLOG:I got inspired to document my own observations in flute-playing and music-making. Also, I thought it's important to pass on the teachings of the great Wilbert Hazelzet, as well as many other mentors who have influenced my artistic visions one way or the other. Enjoy this potpourri of tips, inspirations, and musings. TOPICS:

All

👉"Teddie Talks Traverso" on YouTube

WorkshopsTEACHING:I'm specialized in coaching historical and modern flutists. CONTACT ME directly to set up a session, in person or online. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed