|

Mark Dannenbring reminded me once the concept of experiencing music kinesthetically. It's true that actually, I'd characterize my interpretational style as a combination of employing imagery and feeling a sense of energy or motion.

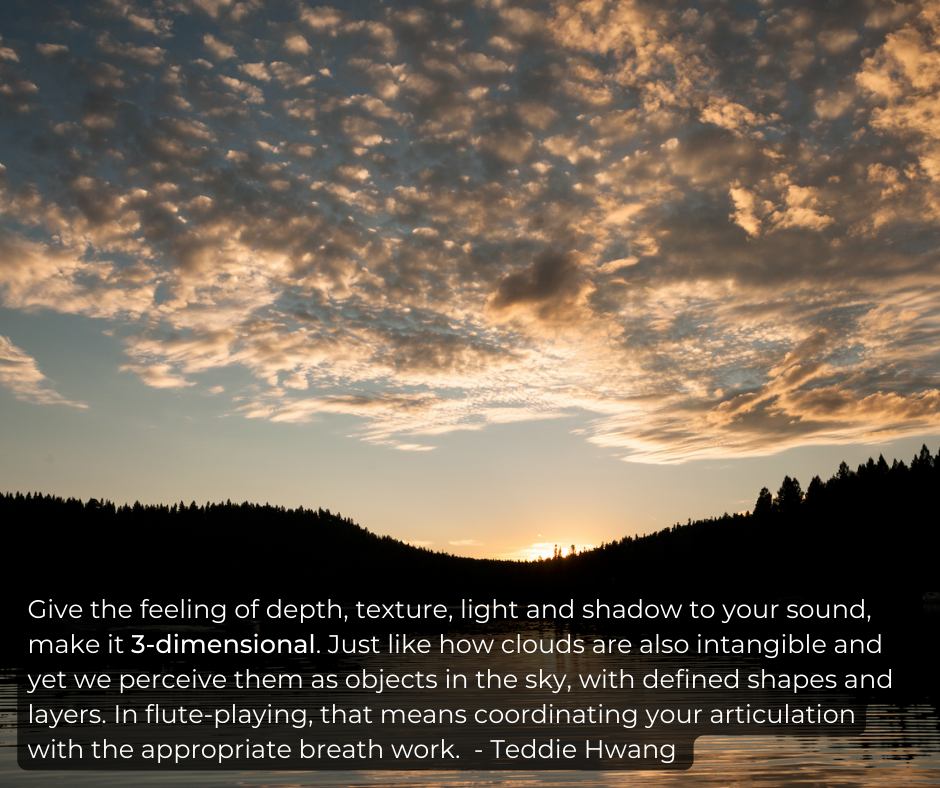

Imagery is something easier and quicker to grasp. Energy, however, is more abstract and also, everyone feels differently. Some people feel more, some less, but when is it too much this way or too little the other way? This is why, for example, that a key element in chamber music is finding people who feel similarly. Pedagogically speaking, imagery is a good place to begin if someone is not that far yet in their development, but ultimately, one needs to feel the movement in order to complete the picture. (pun very much intended!) Art is always about going beyond the natural boundaries of that discipline. A photo is a flat, motionless object, nowadays even mostly virtual. Yet a good photo can express movement, depth, a subject can be jumping out of the frame. Music is no different, as a congregation of sounds is indeed a manifestation of energy, often subtle forms of energy. On top of that, each musical style has a different energy "wavelength". And this is part of our training as musicians - to be in accord with that wavelength, to speak that particular language, all expressed through our unique self.

0 Comments

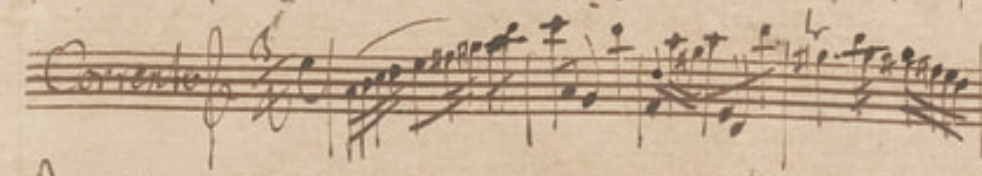

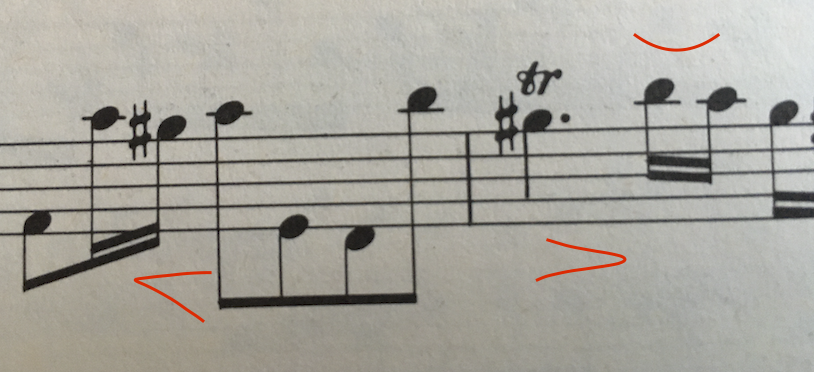

One of the things that makes teaching music so hard is that we often work with exceptions rather than uniformity. For me, teaching a class means a lot of preparation work in finding the right words and expression. I strive to be clear and to find just the right metaphors to hopefully engage as many as possible. A case in point is a situation from my last workshop on J.S. Bach's Corrente from the Partita. I dove right into explaining historical articulation, crafting my language and visuals so that the concepts would appear as comprehensible as possible. Having chosen the passage starting from the half of m. 4 to illustrate articulation and dynamics, I remember thinking to myself that I should not forget to think about how to explain the very opening motif, because that actually goes somewhat against what I tried to illustrate with m. 4-10. Well, in the midst of all my preparations, I forgot.😅 And lo and behold, Cesar asked about it and it would have been a great opportunity to demonstrate how music or art (or everything in life?!) is full of contradictions and exceptions, that rules are only there to somewhat guide you but they don't overwrite everything. So here's for you Cesar! To recap, I offered to my audience a very simple "Quick Tips in Interpreting Melodic Movement". As easy and as over-generalized as it may seem, they really do define how the majority of Western classical music functions and I know it's helpful for many. It goes like this: we crescendo with notes moving up, and decrescendo with notes going down. Cesar's question was whether I would also apply that same concept in the opening bars up to m. 4. Well, yes and no. In principle yes, but not everywhere. The reason being that there is also the question of character and that can often supersede our neat little rules. It would be boring if everything fitted perfectly and it also shows that we have so many tools and elements to work with in music. So while a crescendo is a great thing to do in that first scale going upwards, I actually wouldn't do much nuancing between all those dramatic jumps in m. 2-3. Even if the basic outline of those bars is going down towards m. 4 (C-B-A-G#), there is a definite sense of rambunctiousness through that passage and not really an expression of delicacy. (which then contrasts beautifully with those falling scales starting mid m. 4). There are, however, still some little details we could do: One may also consider to swagger that rhythm just ever so slightly, make it jump out of that low F (which is a terribly weak note on the baroque flute, we'll get to that lower voice in just a bit). I think it's worth staying in this stubborn character and thus only do a slight tapering through the trill, so that the cascades coming afterwards can start soft and have a different affect. OR, you can certainly diminuendo between the B and G#, which will give a softer feel, and use that as an effective repeat.

The lower line implied through the notes going down (A-G-F-E-D): again because of the character, I wouldn't think much about getting softer through those little steps. Stay in that stubbornness. A technical challenge here is to have these very low notes of the baroque flute sound as powerful as the higher notes. Thus, the important thing is to have a good solid sound, it doesn't need to be super loud, just give enough space for the notes to resonate. Don't squeeze with the embouchure or tongue too forcefully. Work more with the breath than anything else. And then, after all that earthiness, you can enjoy tumbling in the air.... A heartfelt THANK YOU to everyone who came to my Corrente workshop on Sunday! I'll admit it was ambitious planning to talk about the Bach Corrente in 30 minutes😅, but I'm really grateful for the interest from around the world, including participants from Asia tuning in at their wee hours. The Traverso Practice Net and I will be gathering people's feedback and we hope to see you again at a future event. Here's one of my messages from the workshop:

I feel a common misconception that people sometimes have about baroque music is that one needs to articulate more. More separated, more clearly, playing 'drier'. This idea doesn't really reflect the true aesthetic of baroque music, which is the speaking quality. It is actually about using a variety of articulations, with slurring included. In historical playing, we use syllables like D or R (hard like in Spanish), in addition to the common T which is most common for modern flute playing. This really gives the player a lot more options to shape notes, as we can adjust infinitely the intensity of the syllable (lighter or more distinct? More forward in the mouth or in the back?) as well as the quality of air used to play in that moment. By quality I mean the characteristic - faster or slower airstream? Loud or soft? Bell-like impulses or more stretched? Brilliant or dark?

The thing with slurring is that it's an "on" or "off" mechanism. The breath can still play a role, but we simply lose those fine shadings we'd otherwise have with T D or R. That doesn't mean, however, that slurring didn't exist or that it's a bad thing to do. There are MANY examples of slurring in baroque music! It all has to do with the interpreter's intention, what is to be expressed in a passage? Which articulation does justice to the intended affect? How are you speaking to your audience? Should it sound easy going or is there a more intense message to be delivered? What kind of profile or texture in sound makes sense here? Make all these decisions a conscious one, based on informed choices. And by including diverse articulation methods AND slurring, we increase our vocabulary in our musical language. |

ABOUT THE BLOG:I got inspired to document my own observations in flute-playing and music-making. Also, I thought it's important to pass on the teachings of the great Wilbert Hazelzet, as well as many other mentors who have influenced my artistic visions one way or the other. Enjoy this potpourri of tips, inspirations, and musings. TOPICS:

All

👉"Teddie Talks Traverso" on YouTube

WorkshopsTEACHING:I'm specialized in coaching historical and modern flutists. CONTACT ME directly to set up a session, in person or online. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed