|

So I thought to continue on my last post about French baroque music. After what I mentioned last, it might seem to you that French music is fussy, superficial, and just not approachable. So why would we want to play this music and why does it attract me?

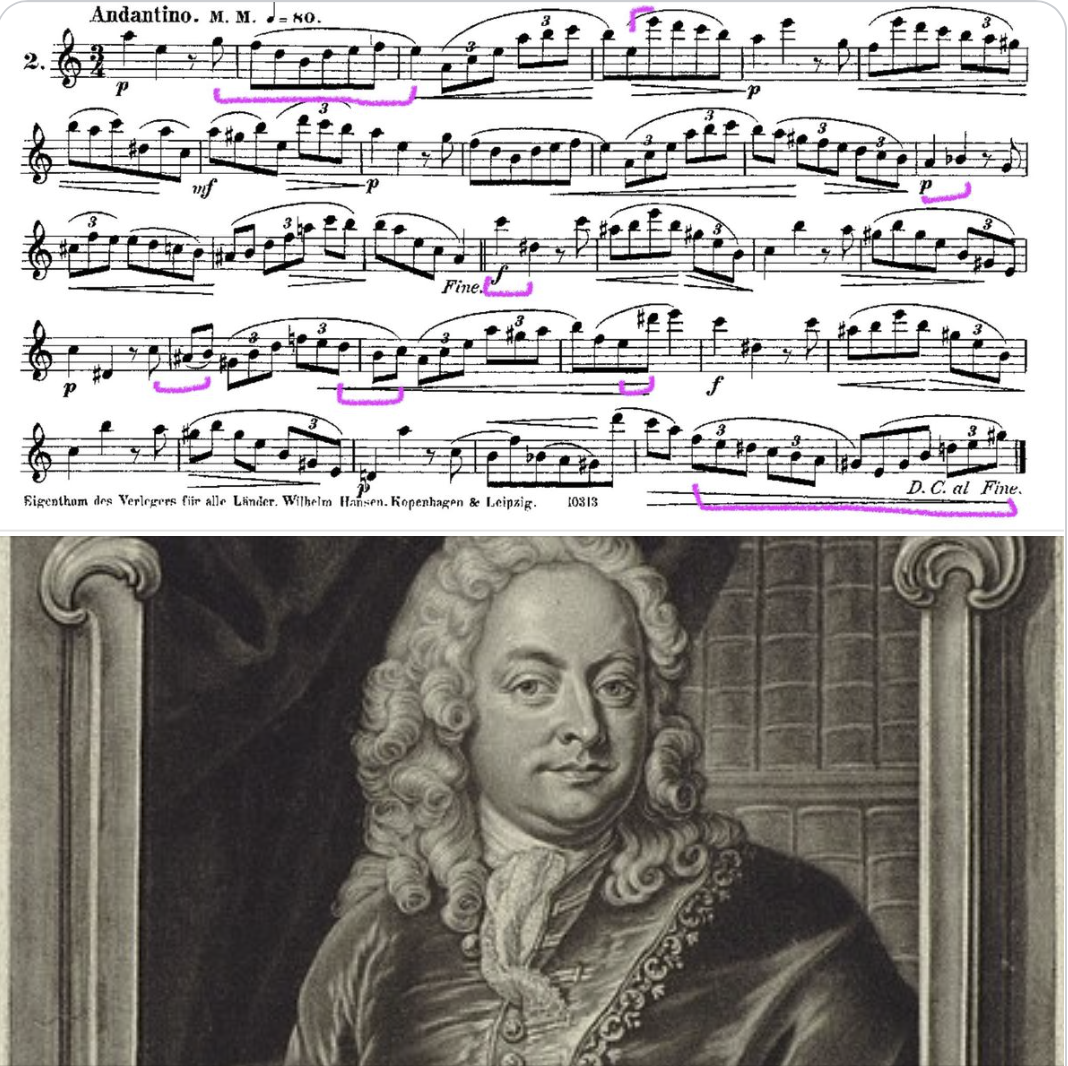

Well, I can’t speak for everyone, but here are my thoughts: I think it IS because French baroque music lies in this gray zone of expressions. To use articulation to create a fine lace of sounds, the sensation of using the breath sparingly and in subtle ways puts me at a place where I feel like I’m floating while playing. The intricate ornamentation isn't just about playing the right notes, but it contributes to an affect and expression. And for me all this is actually something incredibly deep and meaningful, and is one of the main drives for me to play the baroque traverso. It puts me in another dimension, to sing through my flute and taste every phrase, every note. Technically speaking, this means being able to work your air in a very flexible way. Here’s a fun thought: see if you can visualize your breath like a jellyfish moving underwater in slooow motion. Be able to direct the breath, make it undulate according to the phrasing, up to the final wisps of air between notes and at phrase endings. (imagine those like the fine and long tentacles of the jellyfish!) There is a lot of nuanced tapering of sound needed in this music to reflect the commonly open, ambiguous ends of words in the French language. In connection, achieving this effect will also involve the very fine, micro muscles of the embouchure. These techniques need to be learned, of course, and may not come so naturally. Many talk about learning French to understand this, which would indeed be helpful, but perhaps these visualizations can also help people figure out how to translate the language into flute-playing. The above passage from Blavet's Recueil de pièces is an attempt to show how to work the breath in this case. It's impossible to notate exactly what happens, but hopefully this gives an idea. Note also Blavet's indication: tender with a sustained, well-spun sound. I hope you can find the same joy as I experience from French baroque music. 🌬️ Keep playing, keep floating, keep spinning.

0 Comments

Here are some extra-musical concepts for French baroque music, which perhaps some players may find useful. One of my favorite ideas from Wilbert Hazelzet is that he said playing French music is like “walking on eggshells”. Take a moment to imagine if you had to do that....you'll think about how to shift your center and weight so that you'd avoid breaking the eggshells. (or as few as possible!) You couldn't just put your weight all on one foot. That's the same kind of feeling in French baroque music – we're always playing with a bit of reservation, but there are still ways to bring movement and liveliness to the music. Finding that balance is what challenges people of course, it's so much easier to just kind of “pour your heart out” (that's like putting all weight on one foot), but a NUANCED APPROACH to articulation and sound production will help tremendously. It's walking on a fine line and that's what makes this music so exciting.

Another way to think of this is look at French cuisine. In the end, the highest bar to achieve is that the food just tastes simply amazing without necessarily being able to attribute to just one source. Everything works together to make the food (your interpretation) delightful. Your listeners are then just left with pure enjoyment and that's a great sign of artistry! Two pieces that immediately come to mind (although there are countless ones besides these!) are these two movements from Couperin's 2nd Concert Royaux. Graceful, a bit playful, with depth but not too serious, never sounding "rude", charming with occasionally just slightly hinting an edge....all this expressed through the delicate handling of articulation and breath work. A lot of tapering in the sound, listening to what's happening BETWEEN the notes. According to the 18th century German composer and music theorist Johann Mattheson, "joy is the expansion of our soul and thus could best be expressed by large and expanded intervals. Sadness is a contraction of the subtle parts of our body, so the small and smallest intervals are most suitable for this passion." (not quoted word-for-word)

I find the concepts of "expansion of the soul" and the "contraction of the subtle parts of the body" really interesting, and as I'm preparing for my Andersen Etudes workshops, the etude in A minor comes to mind, exactly with the pointed contrasts between large and small intervals. You'll find some poignant places in piano and using more neighboring notes, and the large leaps in forte or part of a crescendo. For me, learning about rhetoric and affect in earlier music made me appreciate later music so much more. I learned to notice details as well as the physical and emotional connections with the notes on the page. The "expansion of the soul" speaks volumes than merely "big interval" or "crescendo". It's not enough just to do something in music, it needs to be internalized and FELT. Thus, it is the joy of flute-playing to physically FEEL those expansions and contractions as our air moves through those intervals. This internal sensation really allows us to experience that feeling of affect and rhetoric on an intense level! 🩷What's a sensation YOU love when playing the flute? In my recent talk together with Amanda Markwick, we delve into the question of what makes the music of J.S. Bach so challenging.

For me, it's definitely the amount of stamina needed, mentally and physically. Playing Bach's music can feel like a test of how well we can coordinate all of our techniques to function together. We first need to have a concept about the music, then arrange all what needs to happen physically: breath work and management – how we regulate our air to produce sound, just like singers do. In addition, Bach's music is notorious for us flutists because we're struggling to find good places to breathe! The question is - where and how to breathe? Articulation – Having our articulation contribute to the affect of the passage. Knowing early articulation methods is a key to that. Navigating difficult keys – Navigating through difficult keys is related to our breath, our embouchure, and coordination with the fingers. Bach wrote some of his greatest works for the flute in the worst keys for us. Think about “Zerfließe mein Herze” from his St. John Passion, or the E major flute sonata. (we don't even get a break in between - no comfort in C# minor!) So all these physical elements need to function together, at the same time, on command to carry out our interpretation. That's a tall order! It IS a challenge but I also see it as motivation. Flute-playing is a physical activity and the practice of it (whether 'practicing' or performing) makes me feel strong and builds confidence in my body. I do enjoy feeling that physical aspect of the challenge and the reward it brings. Another challenge I see with Bach's music is simply finding those important clues which help us in our interpretation. It's like solving a jigsaw puzzle. Because of the common practice back then, things like dynamics and phrasing were mostly not given by the composer (unlike in later music). But that's Bach's trust in us that we're able to nevertheless understand his intentions. Or perhaps we can think of it like a game we play with Bach – he gives us some clues, can we get what he's talking about? Here's a recent post I did on Facebook, reaching out to those who appreciate Rudolf Tutz and Wilbert Hazelzet. It all began with some photos I did with my fancy socks, which people seemed to appreciate. You'll see the connections more clearly though once you read on:

Still no Christmas socks, but I've got two walruses enjoying a starry sky. When I began my historical flute studies in The Hague, I met the renowned Austrian traverso maker Rudolf Tutz for the first time.❤️ I mean this in complete and absolute endearment, and that is, his immense stature and unmistakable moustache reminded me exactly of a walrus 😅....The 415 flute I mostly play on is from him and it has taken me through thick and thin in life. It has a very hard-to-repair crack and I hope I'll never jinx my luck with it.🤞 ✨As the 2nd Advent approaches, I'm reminded of the second movement of JS Bach's B minor sonata for flute and obbligato harpsichord. As Wilbert Hazelzet once so eloquently put it, it's a piece about enlightenment and I think that's such a beautiful concept. Maybe that's what the "Largo e dolce" means - large in our phrasing, in our vision of the music, with a sweet and heartfelt expression. Here's to Bach, the stars, the universe.🌟 You can find me on Facebook under Teddie Hwang Music and Photography. Please like and follow! |

ABOUT THE BLOG:I got inspired to document my own observations in flute-playing and music-making. Also, I thought it's important to pass on the teachings of the great Wilbert Hazelzet, as well as many other mentors who have influenced my artistic visions one way or the other. Enjoy this potpourri of tips, inspirations, and musings. TOPICS:

All

👉"Teddie Talks Traverso" on YouTube

WorkshopsTEACHING:I'm specialized in coaching historical and modern flutists. CONTACT ME directly to set up a session, in person or online. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed