|

So I thought to continue on my last post about French baroque music. After what I mentioned last, it might seem to you that French music is fussy, superficial, and just not approachable. So why would we want to play this music and why does it attract me?

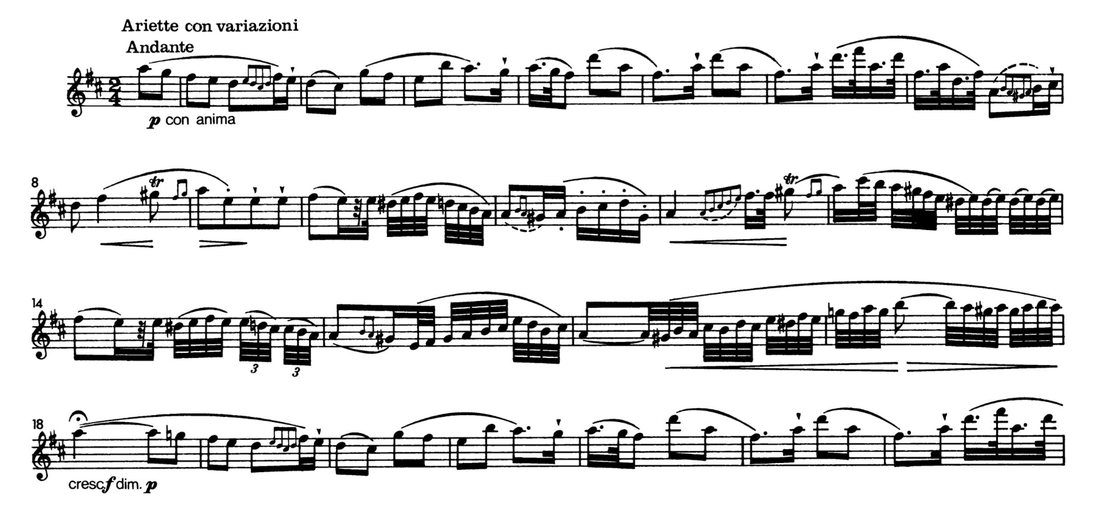

Well, I can’t speak for everyone, but here are my thoughts: I think it IS because French baroque music lies in this gray zone of expressions. To use articulation to create a fine lace of sounds, the sensation of using the breath sparingly and in subtle ways puts me at a place where I feel like I’m floating while playing. The intricate ornamentation isn't just about playing the right notes, but it contributes to an affect and expression. And for me all this is actually something incredibly deep and meaningful, and is one of the main drives for me to play the baroque traverso. It puts me in another dimension, to sing through my flute and taste every phrase, every note. Technically speaking, this means being able to work your air in a very flexible way. Here’s a fun thought: see if you can visualize your breath like a jellyfish moving underwater in slooow motion. Be able to direct the breath, make it undulate according to the phrasing, up to the final wisps of air between notes and at phrase endings. (imagine those like the fine and long tentacles of the jellyfish!) There is a lot of nuanced tapering of sound needed in this music to reflect the commonly open, ambiguous ends of words in the French language. In connection, achieving this effect will also involve the very fine, micro muscles of the embouchure. These techniques need to be learned, of course, and may not come so naturally. Many talk about learning French to understand this, which would indeed be helpful, but perhaps these visualizations can also help people figure out how to translate the language into flute-playing. The above passage from Blavet's Recueil de pièces is an attempt to show how to work the breath in this case. It's impossible to notate exactly what happens, but hopefully this gives an idea. Note also Blavet's indication: tender with a sustained, well-spun sound. I hope you can find the same joy as I experience from French baroque music. 🌬️ Keep playing, keep floating, keep spinning.

0 Comments

Here are some extra-musical concepts for French baroque music, which perhaps some players may find useful. One of my favorite ideas from Wilbert Hazelzet is that he said playing French music is like “walking on eggshells”. Take a moment to imagine if you had to do that....you'll think about how to shift your center and weight so that you'd avoid breaking the eggshells. (or as few as possible!) You couldn't just put your weight all on one foot. That's the same kind of feeling in French baroque music – we're always playing with a bit of reservation, but there are still ways to bring movement and liveliness to the music. Finding that balance is what challenges people of course, it's so much easier to just kind of “pour your heart out” (that's like putting all weight on one foot), but a NUANCED APPROACH to articulation and sound production will help tremendously. It's walking on a fine line and that's what makes this music so exciting.

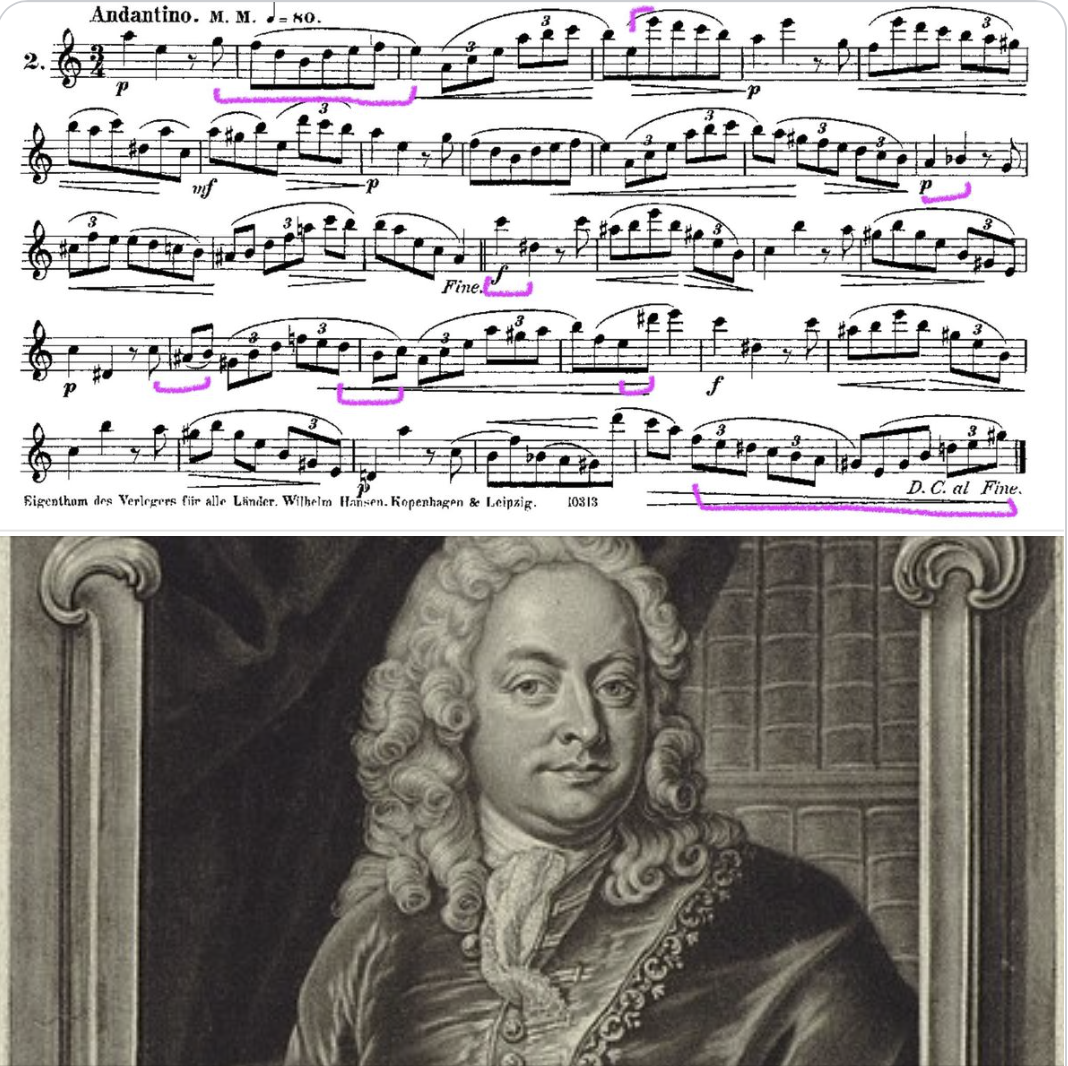

Another way to think of this is look at French cuisine. In the end, the highest bar to achieve is that the food just tastes simply amazing without necessarily being able to attribute to just one source. Everything works together to make the food (your interpretation) delightful. Your listeners are then just left with pure enjoyment and that's a great sign of artistry! Two pieces that immediately come to mind (although there are countless ones besides these!) are these two movements from Couperin's 2nd Concert Royaux. Graceful, a bit playful, with depth but not too serious, never sounding "rude", charming with occasionally just slightly hinting an edge....all this expressed through the delicate handling of articulation and breath work. A lot of tapering in the sound, listening to what's happening BETWEEN the notes. Here's a possible articulation solution for Telemann's B minor Fantasy for solo flute, end of first movement. The 't can either mean closing the sound at the end of a note or to start a note. It means the tongue is back on the palate and ready to go. The alternating blue and red is just to make it easier to read. Notice also I prefer to use a "d" for the low notes for a better and more secure sound production. Remember that how you work your air and the characteristics of particular notes are also important aspects in articulation, so it's not just reliant on the syllable alone. A "t" could potentially also be useful for a soft effect, such as for the high A# at the end since it helps to bring clarity to the otherwise dull-sounding note. With all these differentiations of t, d, r and in combination with variations on how/when to stop the sound, one can truly bring out the "Vivace" of this movement - "lively". I think liveliness through articulation is one of the hallmarks of baroque music and you can see here how effective this is. If you'd play this movement just fast and without any of these nuanced details, then you're missing out on a lot of fun and so is your audience! Try it out and let us know what you think! To hear this passage from a practice session, refer to my video here: Here's the Op. 38 Fantasies by Friedrich Kuhlau. Fantasy Nr. 1 has a nice little variation to the Mozart theme "Batti, batti o bel Masetto" from Don Giovanni.

I'm practicing this for an upcoming performance and it feels nice to flex some modern flute technique! Yesterday, I reminded myself to SLIGHTLY RAISE THE RIGHT HAND if I find myself kind of choking the high notes. So for example, if I'm playing a scale is going up, I'd gradually raise my hand just a bit. That seems to guarantee a more secure way of playing notes like high F# and above. Because this is not the normal range of baroque music, it can feel intimidating. It seems to me that by raising the hand, it's an act of working against fear and making sure we don't clamp down in that moment. If you feel some fear, confront it by standing up and standing proud. Resist feeling apologetic. Also, I try to relax my hands and imagine I'm releasing the note, as opposed to just simply playing/producing the note. If you're experiencing a similar issue, try this out and let me know what you think! What's YOUR tip in confronting fear while flute-playing? According to the 18th century German composer and music theorist Johann Mattheson, "joy is the expansion of our soul and thus could best be expressed by large and expanded intervals. Sadness is a contraction of the subtle parts of our body, so the small and smallest intervals are most suitable for this passion." (not quoted word-for-word)

I find the concepts of "expansion of the soul" and the "contraction of the subtle parts of the body" really interesting, and as I'm preparing for my Andersen Etudes workshops, the etude in A minor comes to mind, exactly with the pointed contrasts between large and small intervals. You'll find some poignant places in piano and using more neighboring notes, and the large leaps in forte or part of a crescendo. For me, learning about rhetoric and affect in earlier music made me appreciate later music so much more. I learned to notice details as well as the physical and emotional connections with the notes on the page. The "expansion of the soul" speaks volumes than merely "big interval" or "crescendo". It's not enough just to do something in music, it needs to be internalized and FELT. Thus, it is the joy of flute-playing to physically FEEL those expansions and contractions as our air moves through those intervals. This internal sensation really allows us to experience that feeling of affect and rhetoric on an intense level! 🩷What's a sensation YOU love when playing the flute? |

ABOUT THE BLOG:I got inspired to document my own observations in flute-playing and music-making. Also, I thought it's important to pass on the teachings of the great Wilbert Hazelzet, as well as many other mentors who have influenced my artistic visions one way or the other. Enjoy this potpourri of tips, inspirations, and musings. TOPICS:

All

👉"Teddie Talks Traverso" on YouTube

WorkshopsTEACHING:I'm specialized in coaching historical and modern flutists. CONTACT ME directly to set up a session, in person or online. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed